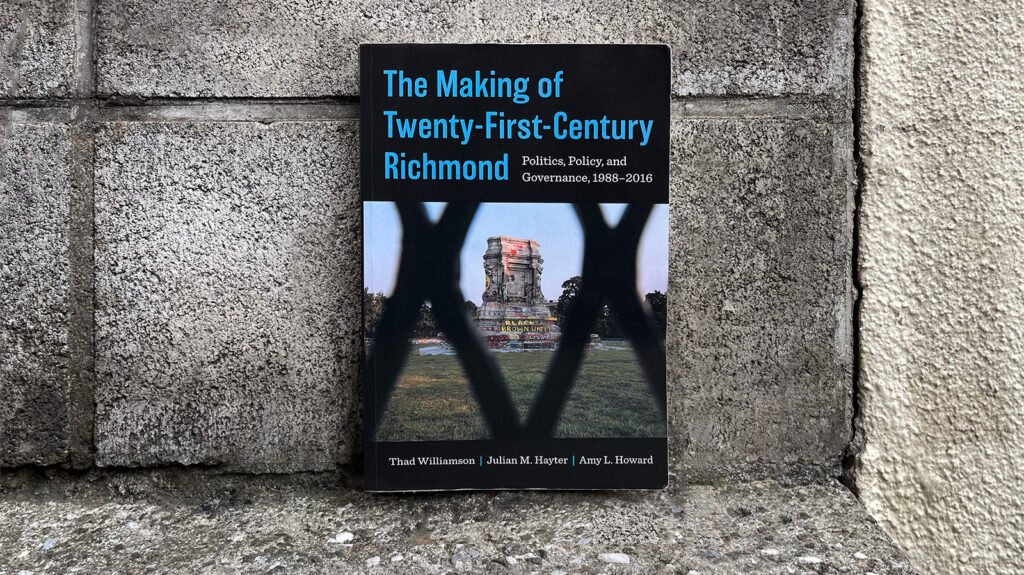

The Making of Twenty-First-Century Richmond: Politics, Policy, and Governance, 1988-2016

Thad Williamson, Julian M. Hayter, Amy L. Howard

University of North Carolina Press

2024

358 pages

John Moeser, a former professor at VCU’s Wilder School of Government, stated that “the story of Richmond is the story of America.” Similar statements have been made by other chroniclers of Richmond over the decades, from Virginius Dabney to Michael Paul Willaims (both Pulitzer-Prize-winning journalists for the Times-Dispatch). The city’s long history mirrors that of the nation, reflecting competing forces of idealism, invention, violence, and discrimination. These arguments often emphasize Richmond’s role in indigenous history, the revolutionary era, the slave trade, the Civil War, and the Jim Crow era.

A new book by University of Richmond faculty Thad Williamson, Julian M. Hayter, and Amy L. Howard extends this line of reasoning to the present, examining Richmond’s fraught efforts to become an economically prosperous and racially just city of the New South. “The Making of Twenty-First-Century Richmond: Politics, Policy, and Governance, 1988-2016” focuses on the actions and inactions of city hall, arguing that the city “exemplifies the challenges facing American metropolitan areas in general, often in magnified form.” Local politics doesn’t happen in a vacuum, and the book carefully positions Richmond’s decisions in the context of regional and state-level politics.

Williamson, Hayter, and Howard are honest, fearless, and correct in placing a large part of the blame for this situation on the region’s deeply entrenched racism. The historical record is incontrovertible: for centuries, the city and state governments used every trick they could think of to disenfranchise the Black community. Richmond’s 1970 annexation of a large portion of Chesterfield County was, for a brief time, successful in maintaining a white majority in the city. But white flight ultimately forced the state legislature to change course. Cities were banned from further expansion, isolated, and marginalized as white residents flowed out to the counties. The book provides rock-solid explanations for why and how the segregated and unjust structure of city-county relations came to be.

As a nation, we suddenly find ourselves in a moment when issues of racial justice and government-led discrimination are suppressed or denied, but that doesn’t make them any less real. The region will never overcome its troubles without a clear-eyed understanding of its own history. Intended or not, this book is a timely response to the moment.

“The Making of Twenty-First-Century Richmond” will be read mostly by students and scholars looking for a straightforward summary of recent city and regional politics. The doggedly organized book seems, at times, like the longest-ever Richmond Times-Dispatch article. A concluding section, titled “Toward a Just Twenty-First-Century Richmond,” provides a more holistic analysis of the city’s politics and prospects, but it would have been helpful to have a narrative form throughout the book. One has to reach page 185 to read the statement: “we see cities as potential sites for enacting democracy and social justice,” which might have been better placed in the first chapter (or even the first sentence).

The book also could have used aggressive sentence-level editing. Take this example: “Indeed, Monument Avenue itself, we know now, was a naked real estate deal under the guise of a City Beautiful initiative.” Setting aside the inaccurate implication that the City Beautiful movement was incompatible with real estate deals, a thing simply cannot be both naked and in a guise. Here’s another: “The agenda sketched above might be ambitious, but with political will and the means to follow through on that will, it is also plausible.” What would be lost in reducing this sentence to: “This agenda, though ambitious, is possible.” ?

Oh well. Not every work of political history has to be a literary phenomenon. And what the book lacks in prose, it makes up for in purpose. Richmond is lucky to have scholars like Williamson, Hayter, and Howard paying such close attention to the workings of city government.

The book advances two general truths about regional governance in the period it covers. First, on issues like inequality, poverty, and sustainability, there has been a bending of the moral arc toward justice, even in the once-intransigent surrounding counties. Second, this improvement in priorities has not always resulted in better outcomes. In order for the machine to run properly, city leadership must have both worthy goals and effective methods of achieving them.

The disconnect between political aspirations and concrete improvements is largely due to the region’s dysfunctional political structure, especially the segregated school system and the unequal distribution of resources between city and county. As the authors write, “Richmond policy makers have been placed in a chronically disadvantageous situation by factors outside their control.”

This doesn’t mean that the authors let city leaders off easy; each administration is carefully scrutinized. But unlike some of the city’s most vocal (and lazy) critics, they insist on historical and political context. “Stronger internal governance might improve the functioning of Richmond’s city government,” the authors write in their conclusion, “but from a larger perspective, this still amounts to making the most of a bad hand.” To really turn the tables, they suggest, the region needs to be open to bold reforms like a unified school district or even a full merger of Richmond, Henrico, and Chesterfield.

For Williamson, Hayter, and Howard, whatever decisions city leaders make must be “conscious but not constrained by the layers of history and complexity” that produced contemporary Richmond. “The Making of Twenty-First-Century Richmond” is a valuable tool in understanding that complexity, and in beginning to overcome it.

DOK

Write a Comment