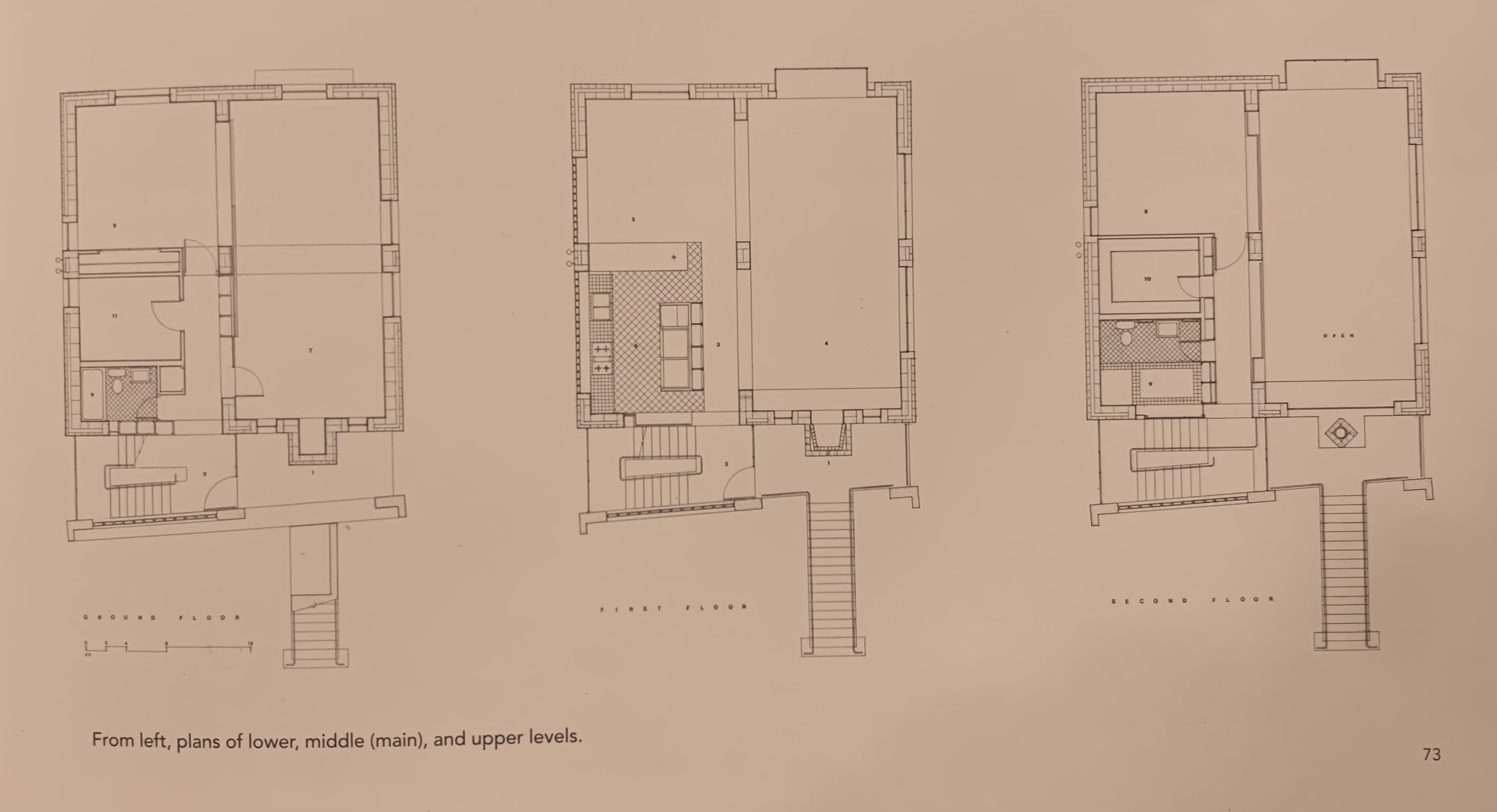

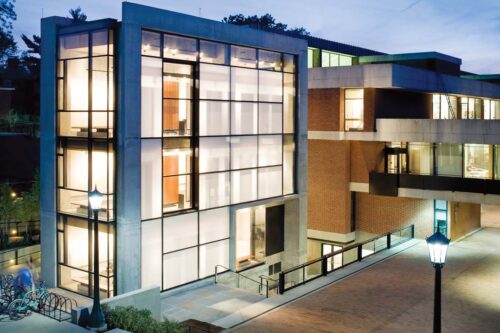

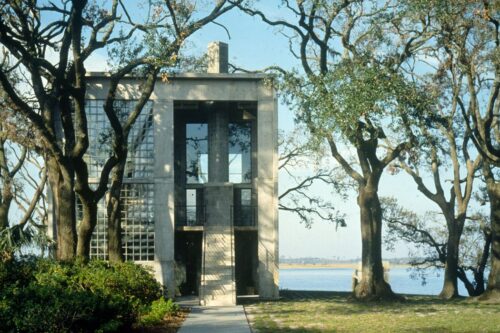

Images captions in order: Beckerdite Scholley House, Campbell Hall at the University of Virginia, Middleton Inn, W. G. Clark House, Croffead House floor plan, Croffead House

Earlier this month, W.G. Clark, one of Virginia’s most accomplished architects, was honored with the 2023 Arnold W. Brunner Memorial Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. The Academy created the prize in 1955 to recognize “an architect of any nationality who has made a significant contribution to architecture as an art.” Clark resides and practices in Charlottesville where, since 1989, he has served as the Edmund Schureman Campbell Professor of Architecture at the University of Virginia.

A native of Louisa County, Va., Clark studied at UVA before working for noted postmodern architects Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown in Philadelphia. He later established a practice in Charleston, South Carolina, where some of his most important commissions were carried out. These include the Middleton Inn (constructed from 1977-85), a spare and stately hotel whose strong plan organization and rhythmic, classically-informed massing recall the work of another famed Philadelphia architect: Louis Kahn. (Kahn taught Venturi and Scott Brown during their studies at the University of Pennsylvania in the 1950s.)

In 1989, Clark completed the Croffead House, a placid waterfront home in South Carolina which established his trademark material palette of concrete and glass block. Over the next three decades of practice, he would recombine these materials with plate glass, concrete block, blackened steel, and lightly finished woods. Throughout his oeuvre, Clark clearly distinguishes between the function of plate glass (for views) and glass block (for light). This distinction is visible in his own home in Charlottesville (1996) and in the Beckerdite Scholley House (2005) in James City County, Va., among other projects.

Despite their crisp modernist detailing, many of Clarks works have an archaic air about them. Compositionally, he emphasizes basic architectural elements such as chimneys and stairs by making them the center of local symmetries. At the same time, he subtly deviates from the historical precedents his buildings reference. At the Croffead House, for instance, the entry stair and symmetrically placed chimney recall the elevated dwellings of the flood-prone lowland South (including, eerily, the architecture of plantations). But the stairs terminate in a blank face, rather than the expected grand door. Visitors must turn to the left to enter, where they will discover that the entire front facade is set off from the main house by a slight angle. This kind of subversion is essential to Clark’s architecture, and it is only possible because the buildings successfully bring to mind forms we are already familiar with.

The later years of Clark’s career produced a substantial body of built work including an addition to Campbell Hall, the home of the UVA School of Architecture. Regrettably, indeed embarrassingly for Richmonders, we have no example of his talents in our own city. That an architect of Clark’s refinement and ability lives just a few miles up the road and yet has been offered no commission here after many decades in practice is, simply, a waste. This neglect was not lost on renowned architectural historian Kenneth Frampton who, in an introduction to a recent book on Clark’s work, described him as a “committed, sensitive, and exceptionally skilled American architect who truly deserves to be better recognized on his own turf.” [1] For Frampton, the failure to reward Clark’s talents with more commissions “testifies to the regrettable provinciality of American regional culture.” [2] Clark’s work draws deeply from the buildings and landscapes of Virginia; it also transcends this context to speak to a wider audience in the way that great art often does. The Brunner Prize awarded this month to W. G. Clark is a fitting recognition of this achievement. It is also a message to Virginians, intended or not, to cultivate the seeds of culture scattered among us as they struggle to reach the light.

Don O’Keefe

Citations

[1] McCarter, R. (2019). Place Matters: The Architecture of Wg Clark. ORO Editions.

[2] Ibid.

Images drawn from McCarter’s Place Matters.

Write a Comment