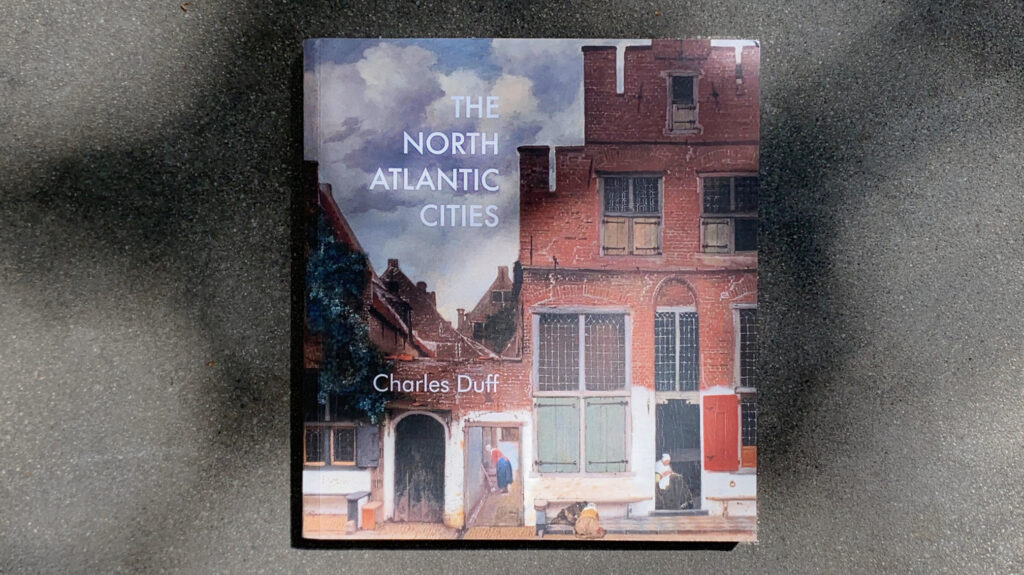

Charles Duff

2019

Bluecoat Press

279 pages

Richmond, like its near neighbors Washington and Baltimore, is a city of row houses, at least in its inner neighborhoods. This urban building block sets Richmond apart from cities like Phoenix, which are almost entirely suburban, and places like Paris, which are composed mostly of multi-family dwellings.

In his recent book, The North Atlantic Cities, Charles Duff chronicles the history of the row house and the cities it helped create, from Amsterdam and London to Boston and Philadelphia. As the title suggests, the focus is on cities on both sides of the North Atlantic Ocean, which Duff convincingly argues can be treated as a coherent architectural region. A product of Europe’s middle class merchant culture in the 17th and 18th centuries, the row house was transmitted to the United States where it developed in new and unexpected ways. From streetcar suburbs to car-centric subdivisions, the row house morphed into the now-familiar form of the detached, single-family home.

Charles Duff, a planner and community developer in Baltimore, writes both as a historian of the row house and an advocate for their continued relevance. His love for the streets and urban spaces of these cities, which he often describes through first hand accounts, suffuses each chapter. This enthusiasm extends throughout the North Atlantic world, from his home-base in Baltimore to the far-flung cities of the Netherlands. “The Dutch,” Duff proclaims, “made the pleasantest cities in the world.”

Richmond is included in Duff’s North Atlantic family—the southernmost outpost of row house urbanism on the eastern seaboard. New Orleans, Cincinnati, San Francisco, and other US cities that lie further inland are excluded from Duff’s study, and so are cities composed of row-house-like buildings in other parts of the world, like Malaysia or Japan. One might quibble with the exact boundaries of this North Atlantic zone (should Pittsburgh be included or not?), but Duff’s definition remains clear because the book is not only a catalogue of a building type, but a narrative of a specific lineage of architectural and urban design. The book is rich with information on the designers, clients, developers, and public figures who shaped these cities, and the economic and political context in which they worked.

Unfortunately for Richmonders, our city is treated only in passing – a relatively minor example of row house urbanism when seen on Duff’s oceanic scale. Still, The North Atlantic Cities presents a wonderful opportunity for us to connect our architectural heritage to that of a broader community, and not only for historical purposes. Row house cities, as Duff stresses repeatedly, are not museums, but living systems, and recent years have brought them a surge of attention. As we consider how best to shape urban growth, Duff’s book suggests that we look to other cities in the North Atlantic family. Could new solutions devised for urban problems in Amsterdam or Boston work in Richmond? Or could we find some precedent in this shared past to which we might refer?

For Richmonders, reading The North Atlantic Cities throws us into sometimes-unflattering contrast with global capitals of commerce and culture. But the book also gives us license to reimagine Richmond and its future. Concerned as we are with the daily bustle of our provincial capital, Richmonders rarely have occasion to consider our city in such esteemed company.

DOK

1 Comment

See the link here for Charles Duff’s upcoming virtual talk at the Branch Museum of Architecture in Design on Wednesday the 31st of March at 6pm! : https://branchmuseum.org/charles-duff/

Write a Comment