This article comes to us from guest writer, Robert Winthrop. Winthrop is partner at Winthrop, Jenkins, and Associates, a Virginia based architecture firm specializing in historic renovation. Historic buildings have also been his focus in numerous writings and lectures. As author of The Architecture of Jackson Ward, Cast and Wrought: The Architectural Metalwork of Downtown Richmond, Virginia, and Architecture in Downtown Richmond, Winthrop has established himself as an authority on the city’s architectural history.

* * *

Richmond’s turn of the 20th century sculptures are dominated by the images of defeated generals on horses. Equestrian sculptures were high status works and Richmond is well supplied with them. The taste for sculpture did not end with Monument Avenue. It continued throughout the 20th century. Though these later works have tended to be ignored, they are of considerable interest.

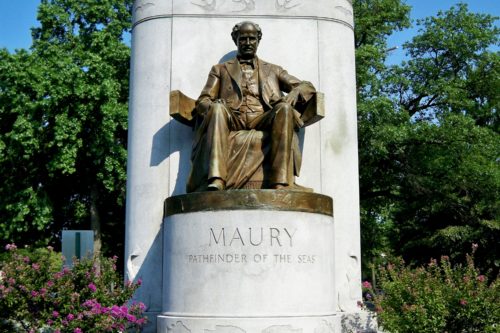

The Matthew Fontaine Maury monument of 1927 represents a break with the traditional, Civil War monument. While it is on Monument Avenue, it is a modern, free-form tribute to Maury’s scientific gifts. It makes no reference to his Civil War experience and features a complex iconography related to the sea. The imagery includes men, women, cows and a dog. While the symbolism is cryptic, it is bold and imaginative. Its sculptor, Frederick William Sievers, had sculpted the rather tame Stonewall Jackson Monument in 1919. Sculpting the Maury monument must have excited him more.

Completed two years later, Thomas Jefferson High School presents an elaborate sculptural program of bas-reliefs and a tribute to our third president as part of its modern, Art Deco architectural treatment. We do not know the name of the sculptor. Sculpture has not played a role in school design since then. The Great Depression caused a near end to building and monumental sculpture in Richmond for ten years.

Architectural sculpture unexpectedly returned to the city in 1941 in the form of the Belgian Building from the New York World’s Fair. The pavilion was for both the small, European nation, Belgium, and for its huge African colony, the Congo.

The architects of the pavilion, Henry Van de Velde, Victor Bourgeois and Leo Stijn were noted modernists. Van de Velde was internationally known and one of the creators of the Art Nouveau movement at the turn of the century. He was the director of the design school that became the Bauhaus. Bourgeois was Belgium’s leading modernist. While the design of the building was modern and minimalist, its exterior was embellished by two major bas-reliefs in terra cotta. They featured scenes of daily life in both Belgium and the Congo. Three sculptors worked on the reliefs, Oscar Jespers, Arthur Puvrez, and Arthur Dupagne.

The Belgian relief shows rather chunky Belgian figures performing various tasks and recreational activities. These are typical of Jespers’ work at the time. This group has conventional social realist imagery, featuring ordinary men and women going about their daily activities.

By contrast, the Congolese relief is elegant and graceful. It reflects the great interest of early 20th century artists in African Art. Dupagne had been in the Congo from 1927-1935 and was noted for his African themed sculpture. His figures are heroic, grand and elegant. His sculptures for the Brussels’ 1958 World’s Fair are clearly related to the Virginia Union works.

The Belgian building was to be disassembled and returned to Belgium, but World War II made this impossible. Therefore, the building was modified and rebuilt in Richmond for Virginia Union University. A historically black university, it was considered an appropriate home for the pavilion.

Leo Friedlander, another World’s Fair sculptor, was a major American artist who created several major works for the 1939 exposition in New York. He specialized in monumental works, several of which are in Richmond.

Friedlander had two modes, one was a hyper-muscular, social realist style. The second style was a slim, lyrical, streamlined style. The muscular style can be seen in the bas-reliefs he provided for the RCA building in New York and the monumental gilded statues that flank the Memorial Bridge in Washington D.C.. The more lyrical style was seen in his statues illustrating the Four Freedoms at the New York World’s Fair. They were tall, elegant figures, and placed at the center of the fair.

Friedlander’s two Richmond works illustrate both styles. His sculpted tribute to Thomas Jefferson on the front of the Jefferson Building on Capitol Square illustrates his muscular style. A chunky Jefferson stares forward, immobile and zombie-like. A series of small reliefs illustrate Jefferson’s life. This building is little known.

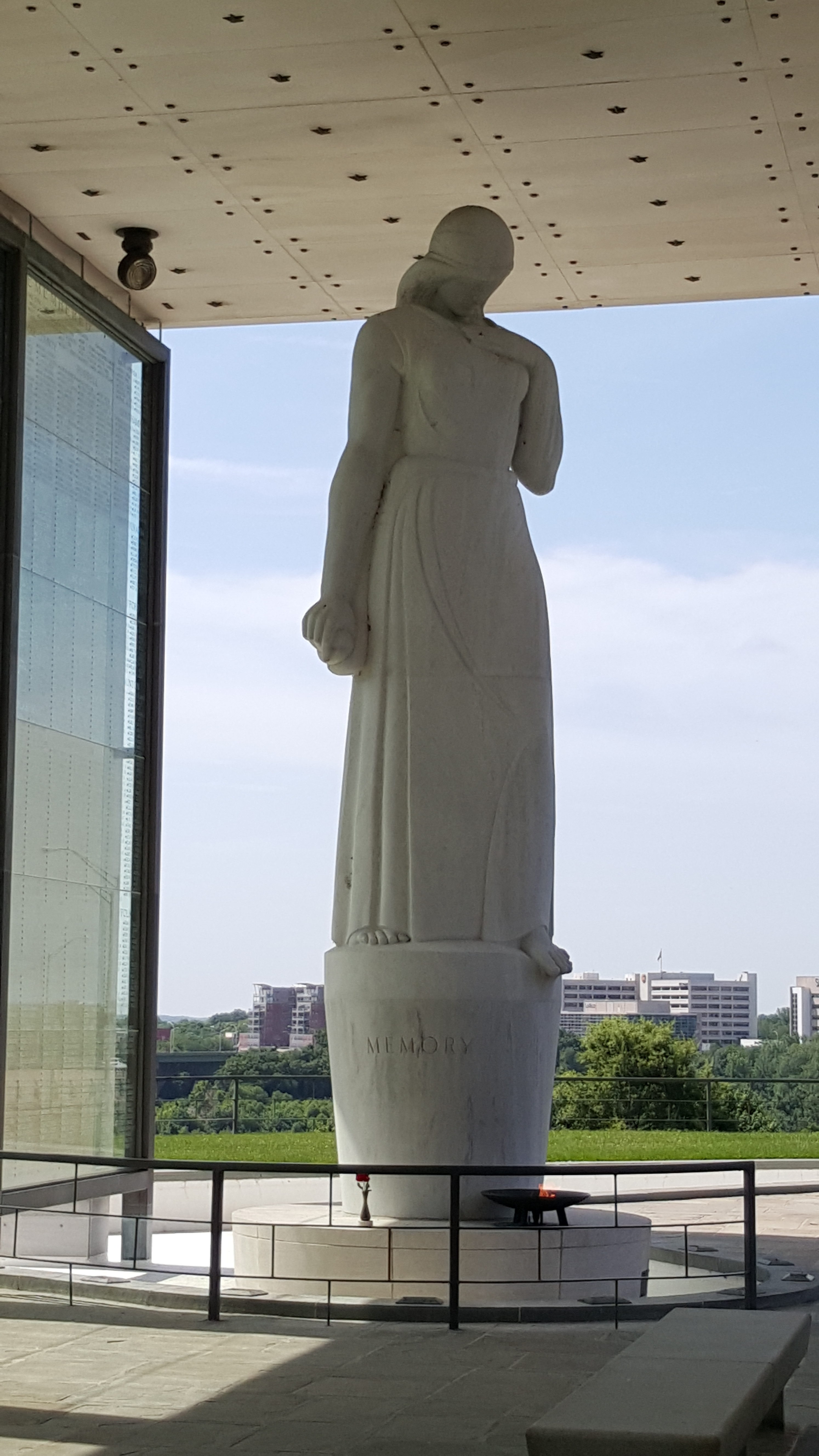

Far more successful is Friedlander’s statue, Memory, which is the focal point of the Virginia War Memorial on Belvidere Street. It was made to honor those who lost their lives in World War II and Korea. The memorial has been expanded to honor veterans of more recent conflicts. Staunton architect S. J. Collins designed the monument in 1950. Completed in 1956, the building forms an architectural frame for Friedlander’s 23-foot-tall sculpture. Memory recalls the elegant character of his Four Freedoms sculptures. The forms of the sculpture are smooth and streamlined. It is restrained and may be one of Friedlander’s most effective works.

Memory is designed to encourage quiet contemplation. Situated on a bluff overlooking the James, she turns her back on the river and faces the names of the dead etched on the glass panels of the memorial. The sculpture represents the opposite sculptural approach to the defeated generals on horseback of the late 19th and early 20th century Monument Ave.

Article and images from Robert P. Winthrop

Write a Comment