Ryan K. Smith

2020

Johns Hopkins University Press

328 pages

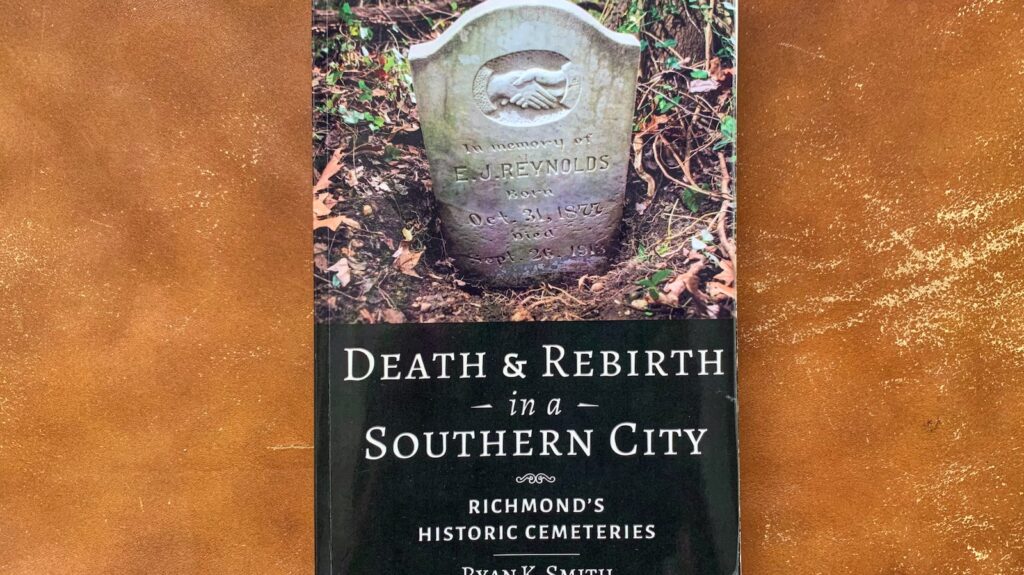

Asian, Latin American, Islamic and other growing Richmond communities “will navigate anew the panorama of revolution, war, gender, art, industry, race, environment, and memory at this fateful city on the James.” This is how Ryan K. Smith, a professor of history at Virginia Commonwealth University closes his thorough, tender and achingly prescient book, “Death & Rebirth in a Southern City: Richmond’s Historic Cemeteries.” As the metropolitan area moves further into the 21st century melding the traditions of emerging religious and ethnic groups, Smith looks back at the intriguing and varied ways in which the city’s different populations have honored its dead in the past.

An overriding take away from “Death and Rebirth” is Smith’s conclusion — as obvious as astute, and certainly poignant in the shadow of Black Lives Matter– that too many of the region’s older Black burial places and cemeteries have suffered tremendously from decades of neglect. This sad state of affairs continues. An April 15, 2023 front page headline and news piece in the Richmond Times-Dispatch reinforced his observations: “State will look into nonprofit tied to city: AG’s office says it is Enrichmond group.” In 2022, a well-established and apparently poorly-managed not-for-profit organization, the Enrichment Foundation, which assisted the city’s Department of Recreation and Parks, suddenly dissolved. Gone. Still to be determined is what happened to the $3 million that the trust held in its accounts for some 85 smaller local civic and cultural organizations. Among the high-and dry groups is the Friends of East End, an organization established in 2013 to preserve two historical African-American cemeteries. Evergreen and East End cemeteries together comprise 76 acres that are the resting place for hundreds of formerly enslaved and free people. After years on the part of many to restore the burial places to a modicum of dignity, the Enrichmond Foundation created a development company to plan how best to rejuvenate the overgrown and dilapidated graveyards (an estimated $19 million endeavor).

“They [Enrichmond] have done enough damage to the cemeteries and to the community they claimed to serve,” Brian Palmer, a founder of the Friends of East End told the newspaper. Palmer is one of many sincere voices in this new history. Smith describes a realistic, but still determined Palmer in his reclamation efforts in a chapter entitled “The Post-Emancipation Uplift Cemeteries.” After working for 18 months, Palmer voiced hope for the effort: “All I could see was tragedy. I was overwhelmed. But once I had enough headstones in me and enough stories, I realized that I can’t save the place as an individual, but I can make an effort.” Palmer told Smith: “We can do this… enough people are having that transformation now. They get it. They understand that this is as important as anything else in the city of Richmond.”

The fate of black cemeteries has captured the hearts of many Richmond area residents recently. There was a proposal to build a minor league baseball park in Shockoe Bottom, probably atop all but forgotten African-American graveyards, paved over with asphalt. Virginia Commonwealth University finally came around to tearing up a huge surface parking lot in Shockoe Valley that obscured graves, probably hundreds of them. More recently, Black graves were discovered underneath the site of a former gas station in North Jackson Ward.

In sharp contrast, Smith points out that many Richmonders take pride in many of the city’s historic white cemeteries. One of these, pristine Hollywood, is considered one of the most romantic and picturesque in the nation. It is also a Confederate Valhalla, where thousands of those who fought the Civil War lie. Often overlooked, Oakwood Cemetery is another burial ground with a sizable Confederate population.

For a book that focuses on how a community respects–or disrespects– its dead, this is a lively and essential read. Smith shares deeply personal and humanistic stories that are richly layered. He examines the city’s Jewish populations who, despite their differing origins in the 18th and 19th centuries, managed to reach an accommodation about burial practices. He describes how Shockoe Hill Cemetery (now Shockoe Cemetery) became a true city of the dead with an aligned street grid and efficiently-spaced family plots. He explains that more modern cemeteries, like Forest Lawn in the East End, express a picturesque spirit while still being designed for efficient maintenance.

Smith brilliantly interweaves deep research with fascinating stories of how utility, economics, racial politics, aesthetics, aspirations, celebration, and memory determine the conditions and fate of these landscapes. The story is as old as time, but Smith’s history is as timely as a newspaper headline.

Edwin Slipek

Citations:

Ryan K. Smith: “Death & Rebirth in a Southern City: Richmond’s Historic Cemeteries,” 2020,

Johns Hopkins University Press.

Write a Comment