This article comes to us from guest writer Robert Winthrop. Winthrop is partner at Winthrop, Jenkins, and Associates, a Virginia based architecture firm specializing in historic renovation. Historic buildings have also been his focus in numerous writings and lectures. As author of The Architecture of Jackson Ward, Cast and Wrought: The Architectural Metalwork of Downtown Richmond, Virginia, and Architecture in Downtown Richmond, Winthrop has established himself as an authority on the city’s architectural history.

* * *

John Eberson was one of the most important theater architects of early 20th Century America. Born in 1875 in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire, he went to high school in Dresden and then attended the University of Vienna before coming to the United Sates in 1901. Dresden and Vienna were major architectural centers, with long histories of distinguished architecture. Both cities were centers for Baroque and Rococo design. These styles were imaginative and featured extravagant ornamentation; traits which are visible in Eberson’s designs.

Eberson is best known as a creator of atmospheric theaters. The interiors of these theaters are treated as open-air fantasy scenes. A fantasy townscape sits under a sky complete with stars and clouds. The visual effect of these theaters is stunning. The architectural expression is Baroque and Rococo with strong Spanish overtones. Eberson wintered in Florida and was greatly impressed by the exotic architecture and gardens he found there.

While there are a few early Spanish style buildings in St. Augustine Florida, Carrere & Hastings’ Ponce De Leon Hotel of 1885-88, the Alcazar of 1889, and other buildings created a particularly extravagant and romantic vision of Spain. Addison Mizner carried on this tradition which also found expression in grand houses such as Viscaya (1914-22) and the Ringling’s Ca’ d’Zan (1926).

A craze for Mission architecture swept the nation after the Panama-Pacific Exposition of 1915. This coincided with the location of the new moving picture industry in Hollywood. Even in staid, traditional Richmond, the Mission Style made an appearance. Duncan Lee’s Richmond Art Company of 1919 is a sophisticated example of the style. It is quiet and restrained.

Richmond’s Loew’s Theater is a superb and typical example of Eberson’s atmospheric theater. It demonstrates no tendency towards academic correctness or restraint. It is wild and the interior is luxuriant. Beautifully restored, it still sparkles. It is strange that, in the period, one could call Loew’s ‘typical.’

All of Eberson’s theaters are equally extravagant. Loew’s distinctive entrance feature is related to the Mission St. Carlos Borromeo in Carmel, California. The star shaped opening in the central gable of the mission reappears above the entrance of the theater in a greatly elaborated form. The theater is a fanciful composition on Mission themes. The ornamentation for his theaters was made by the Michael Angelo Studios. Eberson owned the studios, which was run by his wife, Beatrice Lamb. She was an interior decorator. The complete integration of architecture and ornamentation in the theaters is due to this partnership.

Eberson also designed Art Deco theaters and Moderne buildings, mostly later in his life. He produced comparatively few non-theatrical buildings. He designed three high-rise buildings that were not associated with theaters. The Neils and Mellie Esperson buildings in Houston are particularly distinguished. The finest and most sophisticated of his high-rise buildings is Richmond’s CNB building at 301 West Broad Street.

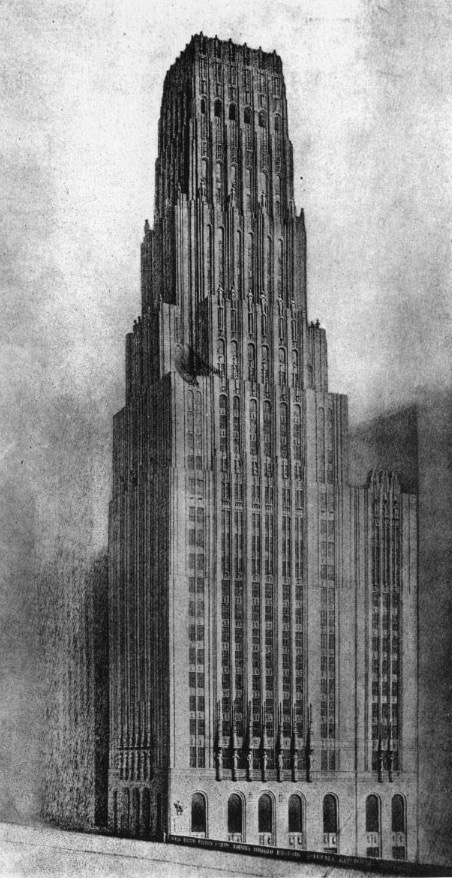

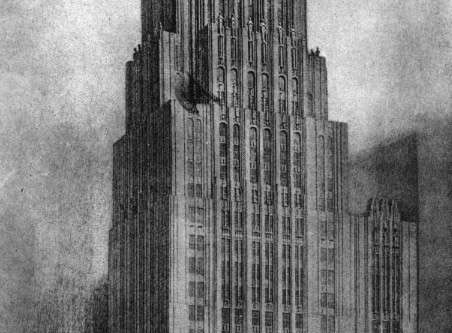

The CNB tower and the associated arcade are rare examples of Eberson’s work. His other tall office buildings are in an elaborate Classic style. The Richmond building is derived from another source, the greatest Finish architect of his generation, Eliel Saarinen. Saarinen won the second place in the competition for the Chicago Tribune headquarters. While it won the second place, the submission was greatly admired and it became influential. It was in a new, distinctly modern style. It had a strong vertical emphasis and the ornamentation was clearly subordinate to the soaring verticality. The building stepped back as it rose. It became a prototype for the Art Deco skyscrapers of the twenties.

The CNB is inspired by Saarinen’s Tribune design; it is not a copy. The verticality of the building reflects Saarinen’s basic effect. By modern standards, The CNB is not a particularly tall building, but it looks tall. The building is sophisticated, elegant, modern and stylish. While it was not in a traditional style, it reflects traditional architectural values such as fine craftsmanship, fine materials and well designed ornamentation.

Surprisingly, the building shows little of the over the top exuberance of his theaters. The bank is assured, sophisticated and skilled. The bank interior is as impressive as the exterior. The banking hall is superb: the ornamentation bold, handsome and modern but also under control. It is the finest Art Deco interior in Richmond. Apparently, Eberson felt that the wild exuberance of his theater interiors was inappropriate for a banking institution.

Eberson’s work could hardly be less like the minimalism of the International Style which became popular in the post-Depression period. His works became stunningly unstylish. It seemed as if there was a concerted effort to demolish the great movie places of the 1920s and some of Eberson’s largest buildings met the wrecking ball. In the 60s Richmond’s Loew’s multicolored interior was spray painted white in an effort to make it more “modern.”

Fortunately, Eberson’s buildings have the ability to inspire affection. The public did not seem to care that the buildings were out of style. The first efforts to save the buildings began in the 1960s and 70s in Akron and Tampa. Richmond’s effort to save Loew’s began in the later 70s and the restored Carpenter Theater opened in 1982. A massive expansion of the facility opened as Richmond CenterStage in 2009.

The renovation of the CNB building and the associated arcade has the potential to transform that part of Broad Street. It is the largest building in the Art Deco sections of Broad and Grace Street. Along with buildings by Carl Lindner, Carneal & Johnston, Carl Messerschmitt and W. C. Pringle, the area represents the Art Deco at its best.

Robert P. Winthrop

Images provided by author

Write a Comment