In the summer of 1958, Edwin Slipek was sitting with his elbows on the window sill, his face pressed close to the glass. From a room high up in the William Penn Hotel in Pittsburgh, he could see the teaming streets below and the belching smokestacks of steel mills in all directions. The sunrise was almost blotted out by smog as he surveyed the ethereal landscape. Then it came: at the age of seven, young Edwin had his “eureka moment,” he later said. “That’s when god told me ‘you must love architecture and city planning!’” He followed the command unwaveringly for the next 68 years.

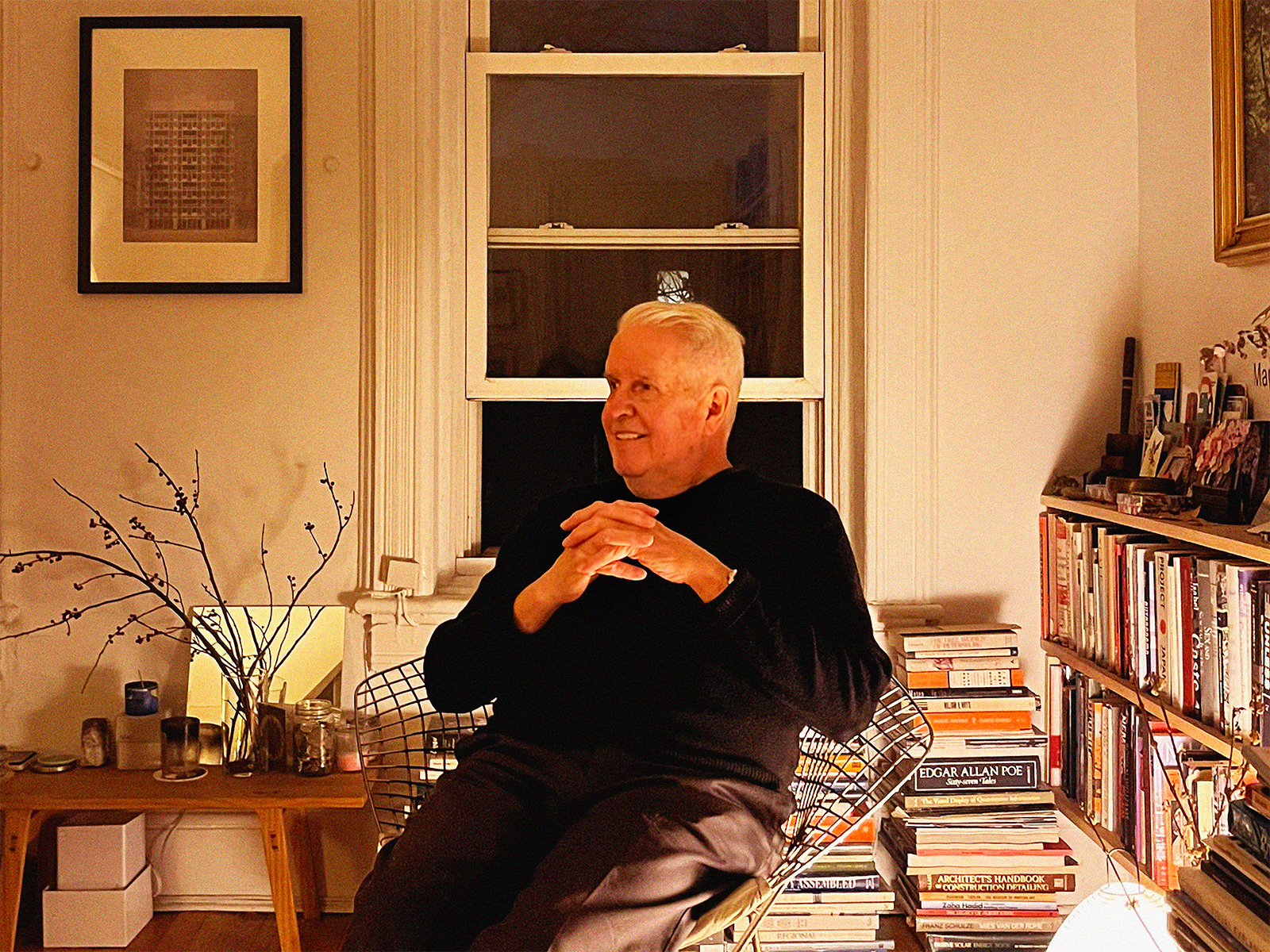

For decades, Edwin “Eddie” Slipek documented, analyzed, encouraged, improved, entertained, and inspired his hometown of Richmond, Virginia. He was best known for his writing and lecturing on architecture, urban planning, and local history. He was the most joyful and enthusiastic person I have ever known, bringing light, energy, and wonder with him wherever he went. He passed away on December 15th after a brief illness.

As engrossed as he was in architecture, that interest was just one manifestation of Eddie’s boundless curiosity. Another was his life long interest in journalism. As a boy he established News of the Neighborhood, a newsletter he delivered to houses around his family’s home on Seminary Avenue in Ginter Park. He was the editor of Woodland Echoes, the newspaper at Nature Camp, a summer camp he attended yearly in Rockbridge County, Virginia. After graduating from John Marshall High School, Eddie attended Boston University in 1968-69 before transferring to Virginia Commonwealth University. There, of course, he became the editor of The Commonwealth Times, the student newspaper, publishing pieces such as an interview with the distinguished Philadelphia architect Louis Kahn.

When Eddie became the architecture critic for The Richmond Mercury in 1973, he was likely the first person ever to hold that title in Virginia. To this day, there are very few cities in the country that have a regularly published writer on architecture. That wasn’t the only way in which the Mercury broke the mold. The hard-hitting young publication set itself in contrast to the city’s conservative dailies, the Times-Dispatch and the News Leader, launching the careers of figures like Lynn Darling, Garrett Epps, Harry Stein, and New York Times theater critic Frank Rich.

From 1974-1984, Eddie entered the corporate world as Director of Communications for Best Products, the retailer founded by Sydney and Francis Lewis. Eddie contributed to the company’s legendary design initiatives, including commissioning graphic design studio Chermayeff & Geismar for its iconic red BEST logo. Other milestones of this era include working with architects James Wines / SITE and Venturi Scott Brown on radical and unprecedented retail stores, commissioning New York firm Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer for the Best Products Headquarters, and helping create the 1979-80 exhibition “Buildings for Best Products” held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This work was widely recognized in design media at the time and remains studied at schools of architecture globally.

This work, together with frequent travel from the late 70s though the 90s, brought Eddie into contact with luminaries such as Edward Albee, Gordon Bunshaft, Leo Castelli, Henry Cobb, Andres Duane, Frank Gehry, Ivan Karp, Spiro Kostov, Lewis Mumford, Laurinda Spear, Andy Warhol, and Tennessee Williams. But more amazing than his connections in the realm of high culture were the lasting bonds he formed with ordinary people in Richmond and beyond. While traveling together in Venice, close friend Sean Storey recounted that Eddie was leaning on a railing along the canal, describing a nearby facade, when a gondolier passed by below. Up from the waters came a cheerful “Eddie!” — a call familiar to all those who traveled with him.

After leaving Best Products, Eddie founded and edited the local culture publication Clue from 1982-83, resulting in a memorable cover story and interview with architect Philip Johnson. Beginning in 1992 he wrote for Style Weekly, and more recently for Richmond Biz-Sense, contributing stories on architecture, culture, history, society, and anything else that illuminated the people and character of Richmond. He also co-founded this publication, ArchitectureRichmond, in 2012, serving as co-editor and frequent contributor for more than 13 years.

His first piece for Style, published in 1992, titled “The Suburbanization of Downtown Richmond,” excoriated the sterile, office-park-like collection of corporate blocks just north of Brown’s Island. The piece continued a decades-long grudge match against the Downtown Expressway, which Eddie helped lead a grassroots campaign against in the early 1970s. Sadly, the effort failed and the highway tore through Richmond, fueling suburban sprawl and destroying hundreds of homes and businesses.

Since his passing, a host of tributes in local publications have demonstrated his far reaching impact on the city, and the astonishing diversity of his pursuits and interests. Bullet points may be the refuge of the lazy writer, but a full accounting would take volumes. Here are just some episodes in Eddie’s impossibly full life:

- Establishing public relations firm Slipek & Co. which planned the world’s largest croquet tournament as part of Monument Avenue’s centennial in 1990

- Running a mid-century furniture shop in Southside in the early 90s called “Mamie and Jackie” (after the First Ladies)

- Bringing the filming of the 1981 Louis Malle film My Dinner with Andre to Richmond’s Jefferson Hotel

- Designing sets for 28 mainstage productions at the Firehouse Theater.

- Serving on boards of numerous local institutions including the Richmond Ballet and the Branch Museum of Design

- Refusing to use email (until pandemic office closures forced him to join the masses), own a television, or carry a cellphone

- Selling his car and relying on the bus for the last decades of his life after his high school students challenged his proclaimed commitment to public transportation

- Curating an exhibition on collegiate gothic architect Ralph Adams Cram, and subsequently authoring “Ralph Adams Cram, the University of Richmond, and the Gothic Style Today” (1997)

The list could go on…

The church was another important part of Eddie’s life. He was a long-time member of Second Presbyterian Church, where he helped those in need through homeless ministry, continuing a pattern of service that began with a mission trip to Mexico when he was just a teen. In 2025, he was elevated to the church vestry, an honor which was deeply meaningful to him.

Eddie considered a life in the ministry – and in politics – but decided against both in the 1960s in part because, as a gay man, he feared his sexuality could be used to destroy his career. During the 1980s and 90s, he lost many friends and his partner to AIDS. He helped stage the “Artists for Life” exhibition at the Milk Bottle Building (then abandoned) followed by a gala at the Empire Theater, with proceeds going toward AIDS-related charities. After all he lost, Eddie still found a way to be positive. He had “survivor’s responsibility,” rather than “survivor’s guilt,” he said. “A responsibility to give back, and to do what I wanted to do.” In later years, Eddie volunteered with ROSMY (now known as Side By Side) to help gay youth find acceptance and peace. He was a nurturing figure in the lives of many.

In fact, Eddie’s greatest impact on Richmond may be through his work as an educator. He lectured to adult audiences in many settings, including at events for the local preservation group Historic Richmond. He also taught courses on the history of art, architecture, and cities for years at Virginia Commonwealth University and Maggie Walker high school, inspiring the careers of many future architects, urban planners, historians, and journalists.

It was in this setting that I first met Eddie. When I arrived at high school, I was reunited with Mario Accordino, a friend from earlier in my childhood with whom I share a love of architecture. As freshmen, we decided to establish an architecture club, but were told we had to have a faculty advisor. As it happened, there was someone at the school who taught architecture to seniors: a Mr. Edwin Slipek. Those who know Eddie can imagine how excited he was when we approached him about our club.

Years later, Eddie joined Mario and me in co-founding ArchitectureRichmond, an online publication of architectural criticism and history. Over the past 13 years, Eddie co-edited the site and authored some 100 articles. Many of them were entries in our “Inventory,” a growing encyclopedia of notable buildings and spaces in Richmond. No matter how many we wrote, we always felt we were just scratching the surface. Among the many plans we have left to complete is a full redesign and relaunch of our website in 2026.

At the time of his death, he was at work on a book review, a neighborhood profile, and several other architectural history pieces for ArchitectureRichmond. Separate from this website, he was also engaged in book projects including a survey on Richmond’s Modern architecture and a biography of architect Duncan Lee (1884–1952) in collaboration with Historic Richmond.

In addition to his writing, Eddie joined me in my architecture practice, O’Keefe & Associates. We had several ongoing projects together, from small buildings to large, speculative visions for the future of Richmond.

Although Eddie was not a designer by training, and spent much of his time studying the past, the question that preoccupied him most was “what’s next?” This quality endeared him not just to Richmond’s historians, but to its journalists and architects.

No matter how unsparing his reviews may have been, architectural criticism rests on the assumption that architecture is important. Eddie sympathized deeply with designers, even if he sometimes subjected them to a public slap on the wrist. He encouraged many young people to enter the design professions, helping to launch the careers of architects and urban planners including Emma Fuller of New York-based Fuller/Overby Architecture, Chris Snowden of Richmond-based Christian Snowden Design, and many others. His guidance was also instrumental to a generation of Richmond journalists, including Rich Griset, a regular writer for Style Weekly now based in London whose work has appeared in The New York Times and The Washington Post.

Eddie was an irreplaceable mentor, as well as my closest collaborator and treasured friend over the last 19 years. We shared many joys together: art, theater, travel, reading, writing, working, dreaming, and most importantly, endless conversation and meandering walks around Richmond. We could finish each other’s sentences, but on occasion we’d argue late into the night (almost exclusively about architecture), with particularly heated discussions culminating in a tearful embrace. Sometimes our conversations followed a familiar format, with me (the younger architect) pushing him (the older critic) to accept some radical new idea. But just as often, the positions were reversed, with Eddie championing the new, the provocative, or the flat-out crazy.

One of our recurring disagreements was about street trees – Eddie felt there were too many of them in Richmond. I observed that Richmond was very hot in the summertime but Eddie countered that, with all the foliage, “you can’t even see the buildings!” Like any great aesthete, Eddie didn’t mind suffering for art. On several occasions, he gleefully threatened to prowl central Richmond in the dead of night with a chainsaw and cut down every tree on Broad Street.

Since the 1990s, Eddie called the Springhill neighborhood of Southside home, but he loved every corner of the city. He grew up as one of six children in Ginter Park. His father, a lawyer, took him on frequent visits to Carytown. His mother, an artist, connected him to family and friends in the West End (and elsewhere in Virginia including rural Blackstone County, where he spent many summers). He lived for years in Church Hill, and claimed to be the first person to live in a loft apartment on Broad Street in Monroe Ward.

I once asked Eddie where he would live if he had a million dollars to spend (at the time this was just enough to afford a home on Monument Avenue). After musing on the benefits of a Monument Avenue mansion, he announced his answer: divide the money and buy a $250,000 home in each of the city’s four quadrants: Northside, Southside, East End, and West End. “I’d move around between the places,” he explained. “Then I’d really know what’s going on.”

Although he traveled widely, lived in Boston in the late 60s, and spent part of his time in New York in the 1980s and 90s, Eddie was a creature of Richmond. His curiosity about the city was insatiable. How does it work? Why is it the way it is? And who made it that way? Eddie wanted to understand it all. I knew he would never truly leave the city, but a couple of years ago I asked him if he had considered doing a short stint away again – a year, perhaps?

“If I was going to live anywhere else, it’d probably be South Beach, or maybe West Hollywood,” he said, picking (I assume) the two most escapist destinations he could think of.

“So, would you? If an opportunity came, would you spend a year away?”

“No,” he said, smiling after a long pause. “I’m just beginning to figure this place out!”

Richmond was his muse. Just days before his passing, Eddie was still out exploring the city, physically and socially. He was a great connector of people and places, inviting us to step out of our everyday lives onto a higher, more contemplative plane. What really makes society tick, and how can we make it work better? How can we do the right thing, and have the time of our lives doing it?

Eddie isn’t with us to ask these questions any longer, but the questions stand. For me, and for many others, his memory will challenge and motivate us for years to come. Perhaps the best way to honor him is to step up onto the plane he invited us to and live as beautifully, joyfully, and fully as he did.

–

–

Don O’Keefe

–

Write a Comment